A Slice of the Sword Life

Shiga’s small town of Gokasho is famed for offering visitors a snap shot back in time to when wealthy merchants inhabited the area. Yet among the museums and vintage memorabilia burns the fire of Masatada Kitagawa – a talented artisan still breathing life into the revered tradition of Japanese sword making.

Through a fortunate connection, I was able to meet Masatada (36) and his swords. I wanted to write about him on Be Wa, as I recognized the cultural significance of his trade and had heard of his talent. Secretly though, I wasn’t much of a sword fanatic. Their mounted, steely aloofness or warrior ‘coolness’ both lost on me. I worried whether my interview would do him justice as I rang the doorbell.

Masatada Kitagawa, a swordsmith from Gokasho, Shiga.

Within moments, a softly spoken and somewhat reserved Masatada appeared. He was wearing the traditional white ‘samue’ outfit of his craft, which I didn’t know then was to help keep him spiritually pure for his efforts ahead. He welcomed me into his tatami mat living room, and to help break the ice, introduced me to a recently completed sword resting on the center table. With gloved hands, he carefully removed it from a quilted sheath his mother had stitched and allowed me to take hold. The weight surprised me (more than I expected for something I’ve seen swung swiftly round on TV period dramas) as did the awe I felt, holding something so esteemed in Japanese culture. It was pretty cool I had to admit, contrary to my awkwardly cautious pose. I leant forward for closer inspection, and Masatada, relaxing into the realm of his work, began to talk with an understated eloquence. I could sense a change coming in the way I felt about swords, and wanted to know more.

The exciting yet cautious chance to hold a katana sword. It felt a bit heavier than I expected but it’s probably just over the 1 kg mark

(Photo: c/o Maki).

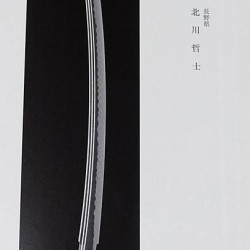

The Bizen ‘wave’ along the sword’s ‘hamon’ area.

The first thing Masatada directed my eyes to was a wavy gleam spanning the length of the sword. It looked like retreating water along a shore line and was enhanced by angling the sword differently to the light. It’s the distinguishing feature of his swords, Masatada added. I searched his face for further hints; as didn’t all swords have this wave? Not so. It’s particular to the rather ornate ‘Bizen’ style of swords he specializes in. With a fondness for taxonomy, I asked how many styles of swords there were. Reaching over to a hefty reference book, Masatada replied ‘five’. Beyond the Bizen style, originating in Okayama prefecture, there are also the similar styles of ‘Yamashiro’ and ‘Yamato’ (from Kyoto and Nara respectively). Both these styles have simpler, cleaner lines and comparing several swords in his book, I took a personal liking to their sleeker, more sophisticated profiles. The other styles are the longer tipped ‘Soshu’ from Kanagawa and the ‘Mino’ style from Gifu. Getting a handle on sword types got the better of me, and I was surprised how fun it had become being able to distinguish and blurt out these style names as Masatada flicked knowingly through his pages, stopping to point out this sword or that. I asked if anyone had thought to combine all the special features from the different sword traditions into the one ultimate sword of swords. He said the techniques for each involve specific focuses on different parts of the sword, so combining these may compromise the overall sword – or, if not, make the sword making process fantastically long. Empathetic that I had a lot to learn, Masatada invited me to into his workshop.

Masatada’s workshop is fairly modest. Accustoming your eyes to the assorted greyness of dimly lit galvanized walls and bags full of charcoal-ish clumps, you’ll find a scattering of simple machines and tools nestled around a tiny working hearth. There’s also a small, central ledge set just high enough for Masatada to work at from a floor cushion – a warm reminder I’m in Japan. It’s here Masatada and his raw materials first come together to make the sword. A sword begins life as a 10kg lump of ‘tamahagane’ steel. This steel is made up of sand iron from Shimane (only authentic Japanese materials are used for the sword) smelted with charcoal. The charcoal adds rigid carbon to the softer iron, converting it into steel. Masatada’s task is to carefully work the distribution of the carbon and iron in the steel to form the two essential parts of the sword. The first part is the outer cutting edge. It’s hard and sharp. The steel here needs higher carbon content. The second part is the sword’s core. It needs to be softer and flexible so the sword won’t snap on impact – there’s less carbon here. To separate the steel into the different levels of hardness required, Masatada pounds it. This has the effect of breaking off the more rigid, carbon concentrated areas which will eventually become the swords edge – once it’s hardened up even further. To do so, he hammers the steel out long and flat (better aligning the carbon) and then, making several small cuts, folds it back onto itself to be hammered out again. He repeats this physically trying process again and again so by the 14th jaw-dropping time, the carbon is nicely aligned and the steel is super hard – so hard in fact, it can’t be engraved. Masatada breaks my astounded gaze by beginning a chalk sketch on the floor. It’s to show how he’ll take the earlier left-over softer steel and sandwich it into this hardened steel (a bit like a hot dog in a bun) to complete the rough work of the sword. I realize that the simple and clean design of a sword hides a fantastic level of complexity and effort. Masatada politely gestures to head above to the next space.

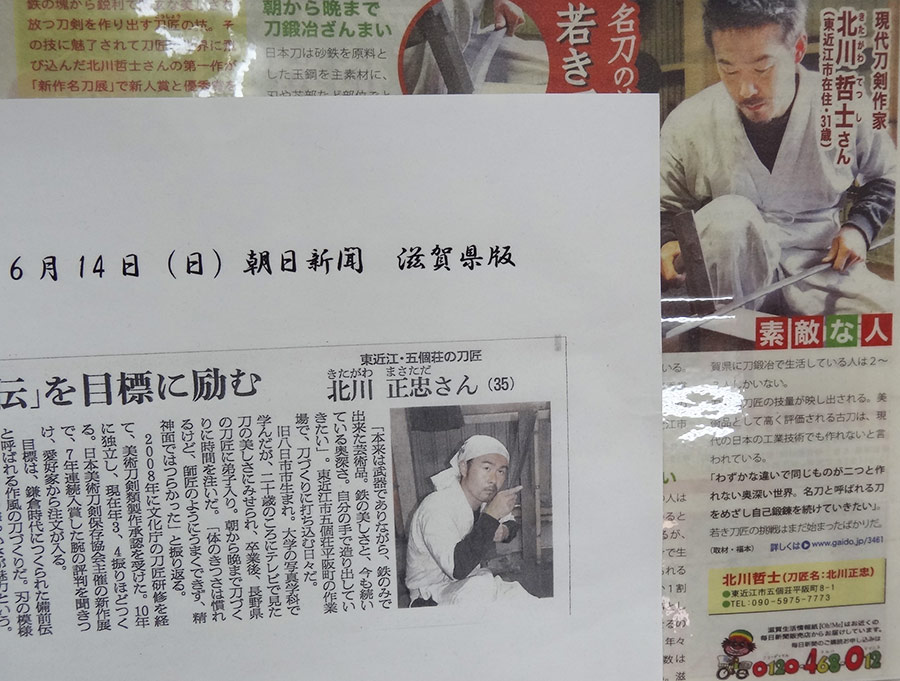

Climbing the light-filled stairwell to Mastada’s second workshop, we enter an airy room whose walls are covered in various types of paper. To the left is a mural of laminated articles his mother has lovingly displayed (somewhat to Masatada’s embarrassment) tracing the growing reputation he’s deservedly earnt. To the right are numerous paper strips, bearing flecked pencil lines, hanging from pegs attached to the wall. I wonder what they’re for. I’m soon to find out. This room is where Masatada refines his swords once they have been hammered into shape to begin the process of making his ‘Bizen’ wave.

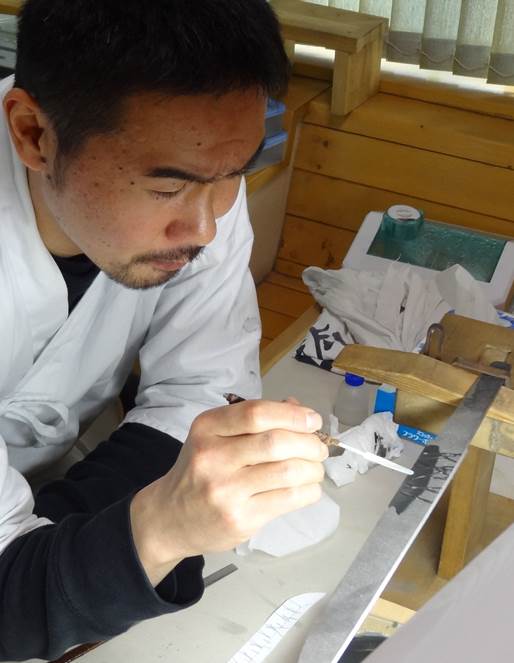

I’d assumed the wave effect was the result of special polishing, to bring out the layering of the earlier forging process, but Masatada informs me it’s not. It’s all to do with clay, at which my love of pottery gladly springs to mind. To make the wave, Masatada delicately spreads a thin layer of liquid clay onto the blade using a small spatula. He then goes back over the clay with the edge of the spatula, making regular small choppy motions. His aim is to work up to a series of prominent, flecked lines that look like abstract blades of swaying grass – wait a minute – the earlier paper strips! The strips are application maps for the clay as the positioning of the flecks must be precise. How these ‘grass’ lines of clay interact is key to the ebb and flow of the resultant wave. Where many lines converge, more clay amasses and where fewer lines meet, less clay. This comes into play when the sword is then fired and thrust into water. Where the clay is thick, the sword cools slowly and where it is thin, fast. This varied cooling rate produces a differential hardening, manifested as a wave, which is both aesthetically and technically stunning. Sword masters back in the Kamakura period reached such heights as to be able to depict natural looking landscapes within the waves of their blades – amazing!

Applying the clay liquid that will determine the ebb and flow of the wave design. Notice the application map on the lower paper strip.

After Masatada’s wave is complete, it’s time for a final polish and then off to the artisans responsible for crafting the handle. All up, it can take 4 months of labor to make a sword. So what about the swordsmith? I’m curious about Masatada’s journey to becoming a swordsmith, or ‘tosho’, I discover.

Masatada’s sword making history goes back around 14 years. The craft first caught his eye on TV while he was studying photography at university. He took no action at the time, but with graduation nearing and his disillusionment with photography growing, the dedicated skill and rich tradition of swordsmithing took further hold. After making some enquiries, he was introduced to Norihiro Miyairi, a renowned swordsmith in Nagano under whom he took an 8 year apprenticeship following graduation. In 2008, after plenty of hard work, technical refinement and long cold winters, Masatada became a registered swordsmith. In 2009 he started winning awards. Up to date, he has won a total of 8 prestigious awards – a trajectory that’s sure to continue (and bring him many clients!). To mark his artistic ascension, Masatada also changed his name (not unusual in highly skilled, traditional fields). Previously, he went by the name Tetsushi (a nice coincidence with the word ‘tetsu’ meaning ‘iron’). His new name of Masatada is the joining of ‘Masa’, coming from the line of his teaching masters, and ‘tada’, coming from the tradition of his sword making style. The kanji for ‘Masa’ (正), it also turns out, has a good engraving aesthetic to it. Masatada engraves his name at the lower handle end once the sword has been finished to perfection. It’s a fate which doesn’t occur for all swords, despite taking all technical precautions. On my visit, Masatada solemnly showed me one of his swords that, during final polishing, had revealed a small blemish in its iron grain. The sword, imperfect, would need to be destroyed. A deep, heartbreaking disappointment, marring the time, effort and care he had invested. There’s also the financial loss, as the sword would have otherwise earned him at least 1 300 000 yen (about $13 000).

Just two of the many laminated stories following Masatada’s sword making progression.

With the demands and risks of sword making, I asked Masatada how rare a profession sword making is in Japan. He estimated between three to four hundred people in the field, but wih only around 10% of them making it their full-time occupation. Within Shiga there are two other known sword makers; one in Eigenji (who is no longer actively producing) and another in Kusatsu. I began to picture myself as a rarer female swordsmith in my own workshop…

It was time for a tea break and we returned to Masatada’s living room. I guess he would have been up for any kind of conversation, but I was eager to hear more on swords. We reopened his reference books and took a look back at some historical pieces.

Japanese swords are an integral icon of Japan, with a history spanning back well over 1000 years. It was interesting to hear from Masatada that the changing design, use and decoration of swords often reflected cultural or warfare shifts over that time. Earlier forms (of the ‘tachi’ style) were often used while fighting on horseback, so their cutting edge was orientated groundward in their casing for speedy ‘draw-to-death’ timeframes. Later, when greater use of foot soldiers was employed, the orientation of the cutting edge flipped (the ‘katana’ style), allowing a quicker over arm swing of the blade onto your opponent. When these two separate styles are mounted for display, the cutting edge is either positioned downwards or upwards respectively.

A photo taken by a fellow admirer of Masatada’s work of the sword being fired.

Sword length also diverged into several styles. Most recognizable is the ‘katana’ or long blade. Next, is the medium-sized ‘wakizashi’. Finally, there’s the smaller ‘tanto’ variety (amusingly the name of a compact Japanese car). Each length is intended to meet one part of the combat spectrum – from outdoor warfare to practical day-to-day protection and then on to closer, more discreet ranges. Masatada confirmed he makes all three lengths.

Combat considerations were not everything it seems, as during the Muromachi period (around 600 years ago) there was a larger split between swords produced for practical use and those for artistic merit. This accounts for the broad range of prices across antique swords, as the sword’s level of craftsmanship can pull rank on its age. Kamakura period swords are often priciest, as this is when the art form flourished under the support of Japan’s top rulers and many elaborate masterpieces were crafted. Surprisingly, sword makers of today, with all forms of modern technology at their disposal, are still largely at a loss as to how to achieve similar artistic heights. An attractive goal none the less for this profession (and culture) centered around the pursuit of perfection.

A miniature masterpiece crafted by Masatada’s mentor. I’m saving my pennies.

As dusk crept across the tatami mats, I asked to head back to Masatada’s workshop to snap a few last photos. I was glad a new window of appreciation into sword making had opened for me, and even had plans forming to order my very own miniature sword for the novelty of using at tea ceremonies to slice my served sweets (turns out the idea to make swords in miniature has already been executed – nooo~!).

Expressing my gratitude to Masatada, I enquired if he had any final thoughts. He said that while swords had a known appreciation as weapons or ‘buki’, he hoped that the artistic beauty and living technical tradition of sword making would gain greater recognition. I was already won over on this latter count. I no longer see swords as fancy sticks of steel – my understanding sinks deeper into the intricacies that lie beneath their clean and cool exteriors. Discovering how the dedicated artisan and raw materials come together through astonishingly complex ancient techniques to form something so pure, simple and long-lasting is awe inspiring. It has given me a lot to think about in terms of committing yourself to cultivating your own skills (though I worry my writing skills here may not live up to the standards of the other Masatada laminated articles). At least I feel I’m on a better path – wasn’t expecting a sword to do that! It’s a satisfying ending as Masatada lowers the roller door to his workshop for another day.

From here, if you would like to know more about Masatada, or contact him about his swords, he has his own website (with some English provided) at http://masatada.jimdo.com/. In ordering one of his swords, prices start from 450 000 yen (about $4,500) for his smaller ‘tanto’ works to beyond 1 300 000 yen for his longer ‘katana’ pieces. There is a wait involved – as his swords continue to win awards, his client list continues to grow among those eager to behold the work of one of this generation’s finest swords makers.

And, if owning your own sword is not a step you’re yet ready to take, there’s also a great series of historic swords on display at the Hikone Castle Museum, Shiga. You can see them live, or even visit them online here. Masatada also attends sword events and seminars in Gokasho from time to time to keep an eye out for (here’s a link to a previous event: http://omishounin.boy.jp/blog/). Time for this article to go back into its digital casing.